Of Her Own Design: Marion Mahony Griffin, Frank Lloyd Wright’s apprentice

By Maureen Callahan

“America’s (and perhaps the world’s) first woman architect who needed no apology in a world of men.” This was a description of Marion Mahony Griffin by the last century’s most renowned architectural critic, Reyner Banham. Griffin was a lady who learned early in life to stand her ground.

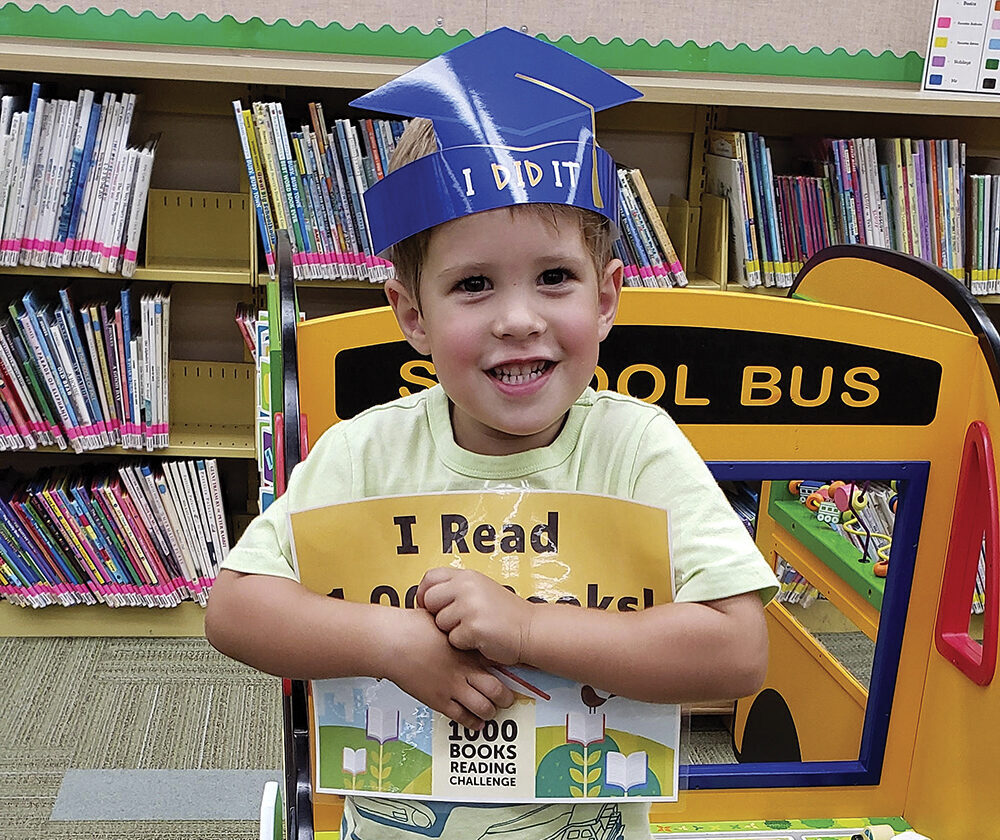

That ground spanned six decades and three continents in a wildly successful career. As the second woman to earn an architectural degree from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), Griffin was also the first registered female architect as Illinois was the first state to register members of this profession officially.

Griffin is considered one of the original members of the American Prairie School – Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic and distinct style. Her designs clearly honor natural settings – a hallmark of the Prairie style that influenced her architecture in countries establishing themselves in the early 20th century.

She likely learned to put fear aside as a small child. Her unpublished autobiography, The Magic of America, recounted Griffin’s mother carrying her out of the flames of the Great Chicago Fire in a laundry basket.

After the fire, Griffin’s family moved to Winnetka. Their house burned down not long afterward. That fire, coupled with the tragedy of her father’s death, forced her family to move back to the city. During this period, Griffin gained much encouragement from positive female role models. A friend of her mother’s recognized Griffin’s potential and offered to send her to school. She enrolled at MIT in 1890, where a male cousin had studied.

Her education and career are appropriately placed in the frenzy of progress and growth that rose out of the ashes of the moment. Griffin designed with an eye toward the future. Her senior thesis, “The House and Studio of a Painter,” was well ahead of its time. The rendering placed a home adjoining an artist’s studio with a courtyard enclosed by colonnades.

After graduation, Griffin went to work with her cousin at his Loop firm. For unknown reasons, she was dismissed from the job just under two years later. Luckily, when that proverbial window closed, a door opened in the office of Frank Lloyd Wright, another young contemporary who offered her a job.

Griffin built her career by working for Wright on and off over the next 14 years in various locations.

A co-worker recounted that Griffin was the most talented member of Frank Lloyd Wright’s staff and that it was doubtful the studio, then or later, produced anyone of superior skill. By today’s standards, Griffin would likely have held the title “head designer.” As Wright finished projects, he often held informal competitions in the office for his staff’s opinions on the placement of materials, like furnishings, mosaics, and stained glass, to his renderings. Griffin almost always won, amplifying her excellent design style.

She has been cited as the greatest architectural delineator of her generation, because of her superb images. A project she completed while in Wright’s employment was deemed “one of the three most influential architectural tretises of the twentieth century.” Unfortunately, the project was from Wright’s years in Germany and not published until much later – too late for Griffin to gain timely accolades. Historians credit Griffin with at least half of the

endeavor’s drawings in Wright’s portfolio, however.

In 1911, Griffin married Walter Burley Griffin, whom she had met while working in Wright’s firm. The pair combined their efforts on hundreds of international projects. Among the most memorable was the duo’s award-winning planned city design for the new national capital in Canberra, Australia. Critics of the day were shocked to see a virtually unknown American woman capture such a distinguished honor.

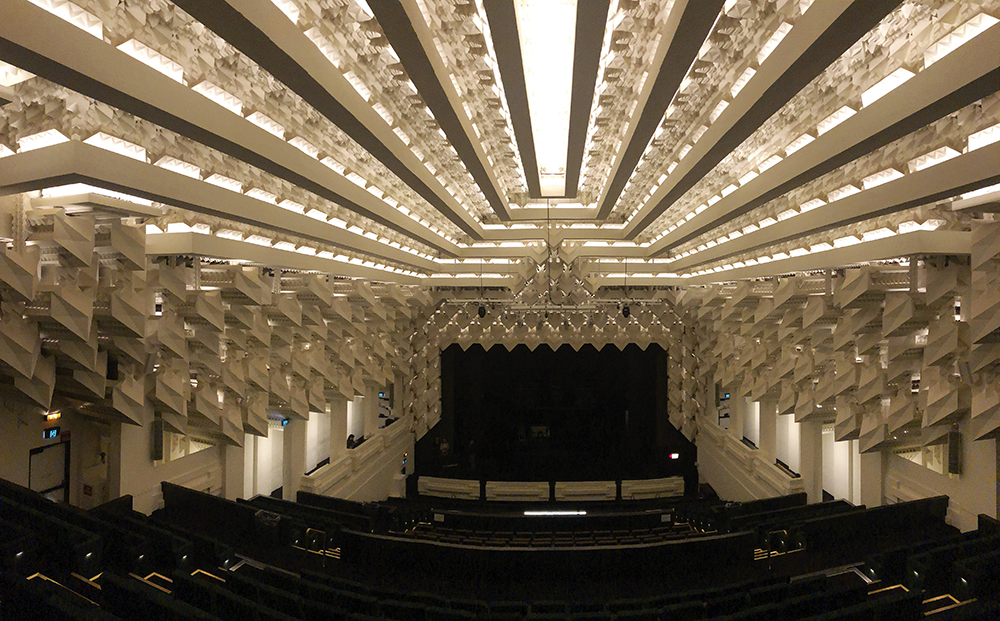

The Griffins continued to collaborate on town plans and landscape designs, colleges, homes, theaters, and restaurants while they lived down under. In 1924, they drew the plans for the Capitol Theater in Melbourne. They were also instrumental in saving Castlecrag – one of Sydney’s most beautiful seaside neighborhoods where the couple had settled – from rampant development. Marion retired shortly thereafter and began artistically documenting Australia’s rugged and unique landscape.

The Great Depression interrupted her so-journ, however, as a large amount of money was needed to save Castlecrag. Opportunities to raise funds knocked when Walter was offered several commissions in India, including the library of the University of Lucknow. He accepted further projects there and influenced Marion to come out of retirement to help him. Marion agreed and sailed to India in 1936 to meet him. They worked together until Walter’s sudden death the following year.

Marion intended to stay in India to see the projects through. However, she was forced to return to Sydney the following year to close out Walter’s business affairs. Marion returned to Chicago in the late 30s. Her second attempt at retirement saw her continue to design, lecture, and write, including the unpublished autobiography of the couple’s life and work.

Marion Mahoney Griffin’s extraordinary portfolio is largely unknown in this country, likely due to the sprawling locations of her projects. Her local design credits include All Souls Unitarian Church in Evanston (1903), Millikin Place, a housing development in Decatur, IL (1909-11), and several homes, one of which was for Henry Ford but remained unbuilt (1912).

Griffin passed away in 1961. She is buried in Chicago’s Graceland Cemetery.

Capitol Theatre, Melbourne. Photo by Michael Thomson

The Robert Mueller House, Decatur, IL, designed by Marion Mahony Griffin. Photo courtesy of Mati Maldre Photography