Out of the ashes: Six and a half decades later, Chicagoans still commemorate Our Lady of the Angels school fire

By Maureen Callahan

The first day of December ushers in the holiday season. It’s a promise of happiness and celebration. But it’s also the day that Chicagoans pause to honor the memory of 92 children and three nuns who perished in a fire at Our Lady of the Angels School (OLAS) on the city’s near west side.

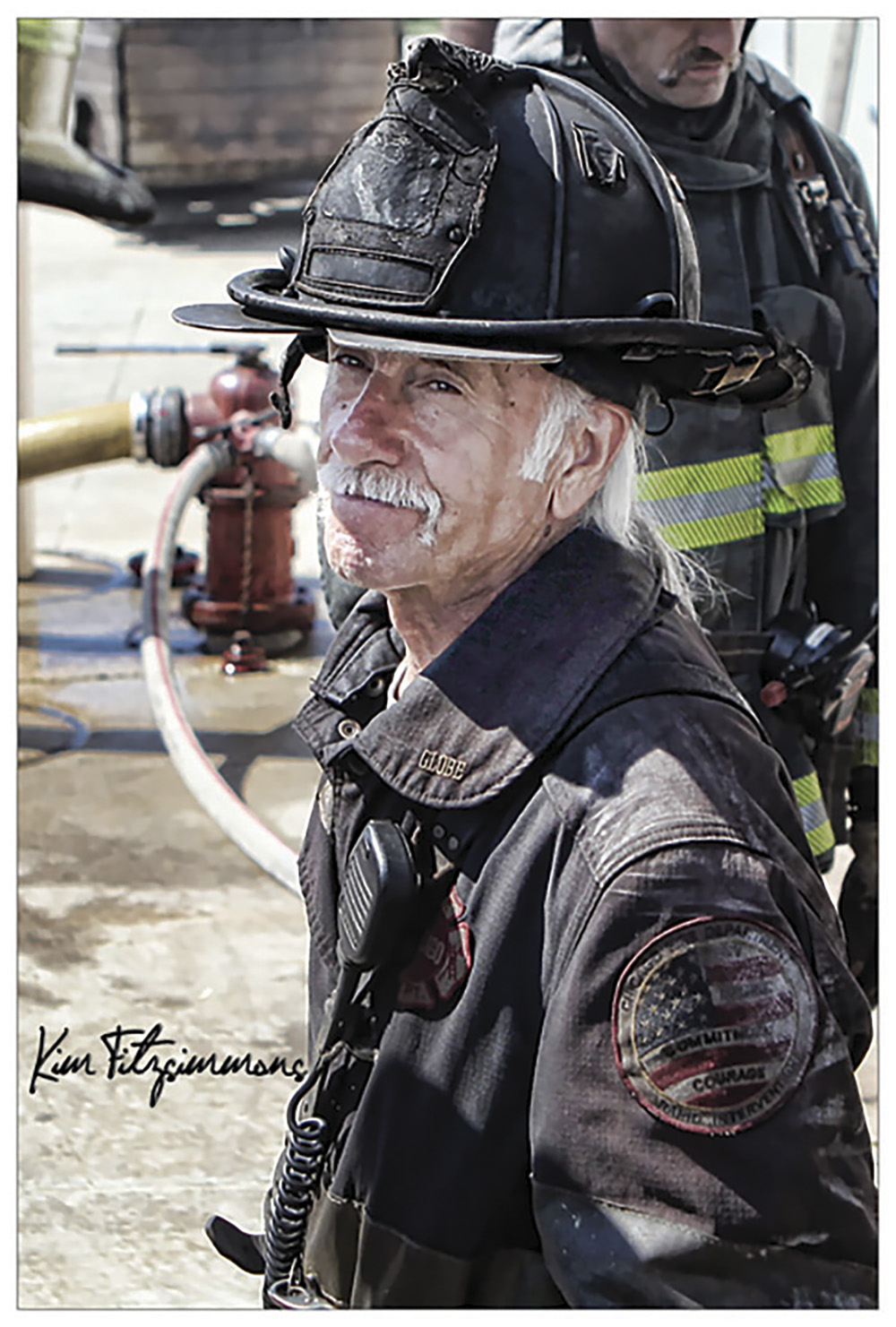

The day was December 1st, 1958. This year marks the 65th anniversary of the day Chicago cried- one of the darkest days in our city’s history. First-grader Michael Mason went on to eventually become a Lieutenant in the Downers Grove Fire Department. He escaped the school as it was burning.

Six and a half decades later, Lieutenant Mason recounted his memories of one of the deadliest fires in American history with Contributing Editor Maureen Callahan:

Lieutenant Mason founded RICO Fire Rescue, Inc.

People always ask if I became a firefighter because of the [Our Lady of the Angels School] fire. To be honest, in the beginning, the answer was ‘no.’ After I got into the fire service, however, I realized more and more what that school fire meant to firefighters. I came to appreciate the aftermath of that school fire and the effect it had on many things.

I still have some recollection of that Friday afternoon. I was in first grade. It was almost time for the school day to end. My classmates and I sensed something was wrong because the nuns were scurrying around nervously. Some kids said they smelled smoke, but nobody in my class saw anything.

After the fire was investigated, we learned the path it took. We figured out that it had been burning in the ceiling above our heads, but we didn’t know. The nun that taught us rounded us up to go outside, but she didn’t have us get our coats. It was freezing outside that day.

As soon as we exited the building, the smell of smoke and burning wood was overpowering. There was mass chaos. People were screaming. Glass shattered. Parents in the neighborhood saw the footage on TV and ran to the school to try to find their children. There were people running everywhere, shouting their kids’ names, trying desperately to locate them from the ground outside their classrooms.

I heard a loud banging noise and turned to see the firemen trying to break through a wrought iron fence outside the school. It was later learned that their arrival was delayed due to an erroneous school address given to the first responders by the person who initially called in the emergency. Meanwhile, smoke poured out of the building. I saw a fireman running with a little girl thrown over his shoulder.

People brought ladders from their home garages and put them up to classroom windows. Kids jumped from second-story windows- some to their death and some to lifelong injuries. Inside, students piled up in front of classroom windowsills as they climbed over one another in an effort to escape.

Firemen recounted having to reach far down inside the windows to grab the children- mostly boys because their belt buckles gave them something to grab. They pulled them out a few at a time and ran them down the ladders. As the fire raged hotter and hotter, they saw time running out and began dropping the children off the ladders as soon as they pulled them out, reasoning that injury was better than death.

92 students and three nuns perished in one of America’s deadliest school fires.

The near west side was a heavily Italian neighborhood at the time. Families were very close. Neighbors who lived adjacent to the school opened their doors to pull children inside to shield them from the horrific vision.

I walked to school every day with my cousins. That day, I went to our usual meeting place in front of the convent, but they weren’t there. There were so many people. It was bedlam! An elderly man picked me up so I could see what was going on. I’m honestly not sure how I got home that day, but I never found my cousins.

“After I got into the fire service, I realized more and more the significance the [Our Lady of the Angels school] fire had to fire fighters. A lot changed after that fire.”

-Lieutenant Michael Mason, Downers Grove Fire Department, Retired, and Our Lady of the Angels School fire survivor

When I got back to my family’s apartment, my grandmother, who watched my sister and me during the day, was in her rocking chair with her rosary in her hands, watching the footage on TV. Not long after, my mom raced in the door and grabbed me. I still remember how hard she hugged me.

People always call me a survivor, but I usually just say I was a witness. There are actual survivors with much worse memories than mine. Another survivor who became the Fire Chief of Elgin was in the north wing, which took the initial brunt of the fire.

Those were the third and fifth-grade classrooms- they got the worst of it. He remembers hitting the ground and crawling. He barely made it out. Many of the kids in that wing didn’t make it.

I don’t think anybody in the city slept that night, but definitely not in my neighborhood. You could hear parents wailing in their houses from the street. The smell of smoke was heavy in the air, and sirens continued all night as the firefighters fought the raging flames.

The next day was Saturday, and the weather was warmer. I wanted to play outside. I remember walking down Springfield Avenue, not being able to find my playmates. A friend of mine lived in the apartment above me. I never saw him again. He just wasn’t there anymore. I found out years later he died in the fire.

Ninety-two children from within a mile and a half radius died the day OLAS burned down. Grief hung in the air. The neighborhood fell apart. Nobody knew what to say to one another, so they didn’t say anything. The community went into a terrible depression.

Our Lady Help of Christians- the next Catholic school over from OLAS- put their own students on a special schedule and took in a bunch of OLAS kids. Others were farmed out to public schools while they waited for the new school to be built.

It took two years. My family hung around for a few more years. By that time, a bunch of families had moved out to Elmwood Park. They couldn’t bear to stay in the neighborhood with all those memories. That’s what my family did after I finished sixth grade.

The really weird thing was that nobody in the school, or the neighborhood, talked about the fire. When the new OLAS school was built, there was no monument, no plaque- nothing to commemorate the lives lost in the fire. The nuns never mentioned it again.

For many years on December 1st, Holy Family Church in Roosevelt Square- the city’s Fire Department Parish- held a mass for survivors of the OLAS school fire. For years, I attended it with my firemen buddies from Chicago, but after a while, I stopped going. I had to move on.

RICO teaches firefighters maneuvers and techniques on how to rescue themselves during fires and collapses.

Out of the ashes of this mind-numbing disaster, however, rose a series of improvements for school designs and fire safety- Life Safety Code 101. These improvements were implemented not only for school buildings but also for public buildings.

The new code changed the materials of which schools are built. OLAS, like many schools of the day, had much highly varnished wood that was very flammable. Safer building materials became a requirement for public buildings. Previous to the code, there was often no way to tell if a fire was brewing until it was visible.

Alarms for early detection, sprinkler systems, and fire doors and windows became mandatory. Windowsill heights may not exceed 44 inches off the floor, so they may be easily egressed in case of fire. There cannot be any locked gates; everything must be accessible to emergency personnel.

Although Mason believes he did not necessarily become a firefighter because of this tragic childhood event, he now realizes that it somehow helped steer his career. In his early twenties, he lived as a jazz musician in the city.

“A few of my buddies were with the Chicago Fire Department (CFD),” said Mason. “They got me to ride along on a few of their calls. They always thought I would make a good firefighter, but I thought they were nuts,” he laughed.

All at once, Mason “was hooked.” He began studying to be a medic in the late 70s and entered Boston’s Fire Academy, as CFD was on strike during the Jane Burn administration. After graduation, he moved back to the area when a position became available in Downers Grove.

Mason now has 42 years of fire service under his belt. The majority of this experience was in the actual fighting of fires, from which he is now retired. But he is still in the game. Some years back, he founded RICO Fire and Rescue Incorporated.

The acronym stands for Rapid Intervention Company Operations. Put simply, it’s a class that teaches firefighters maneuvers and techniques on how to rescue themselves during fires and collapses.

“I offer the class during the week of 9/11 every year because of that tragic event,” said Mason. “Firefighters come from all over the world to learn this.”

Also an award-winning jazz musician, Mason collaborated with several other musicians to create Angels of Fire, a CD of music that commemorates the OLAS fire, told through a series of a dozen songs.

All proceeds benefit I Am Me Camp (formerly known as Burn Camp), the Illinois Fire Safety Alliance’s children’s summer camp for fire survivors.

“Five survivors of the OLAS fire went on to become firemen,” said Mason. “I don’t think I was necessarily influenced by the fire to join the fire service, but later, I think I indirectly came to know why I went down this road and then used it as a purpose,” Mason believes.

Lieutenant Michael Mason, Downers Grove Fire Department, Retired